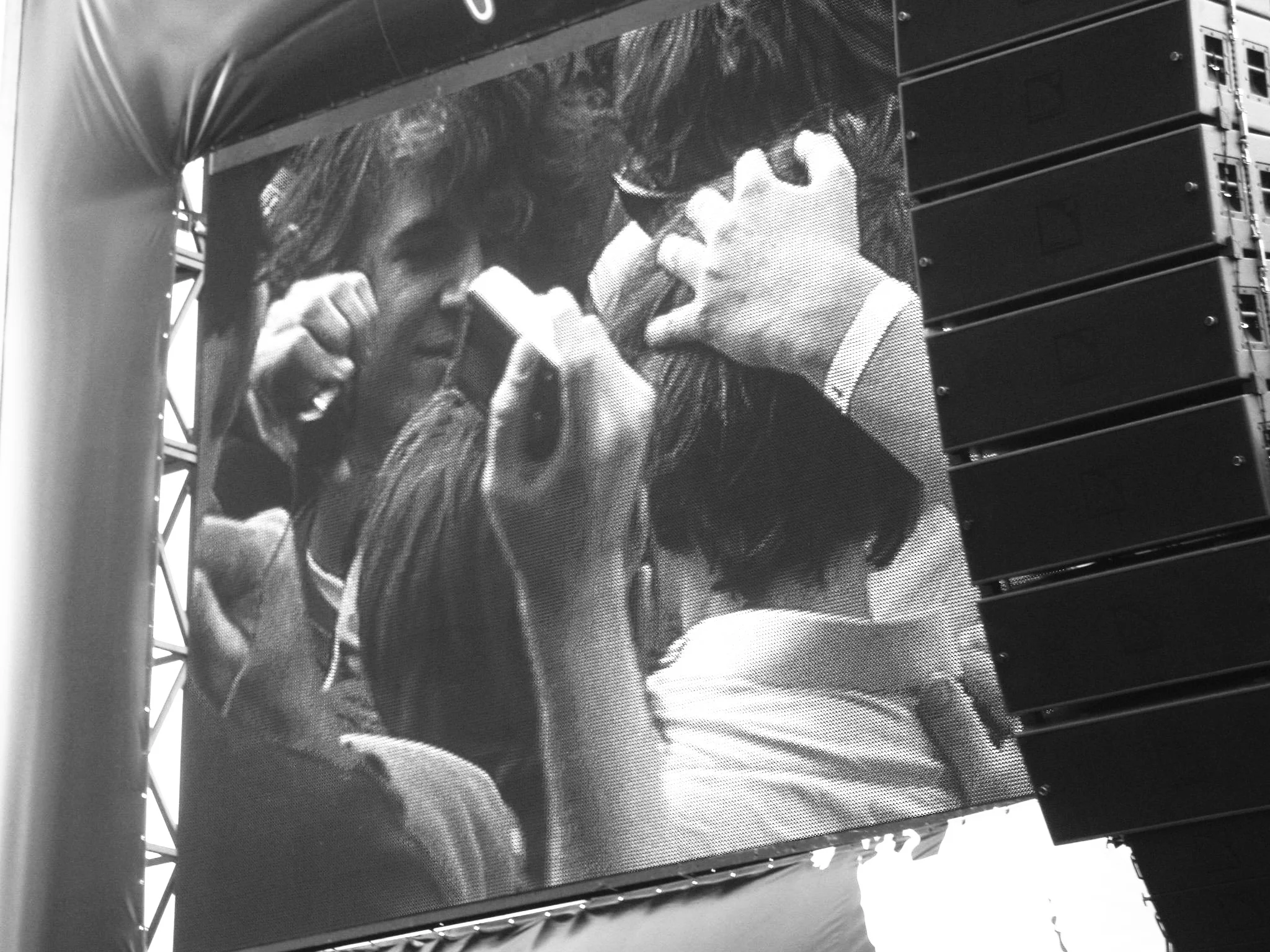

Iggy Pop at the Big Day Out in 2006.

Coolhunting

Pop Brands: Branding, Popular Music and Young People was published by Peter Lang (New York) in 2010. In the book I examine the relationships between brands, cultural life and digital media. I've also taken up these ideas in articles on how brands operate as open-ended social processes, the relationships between brands and algorithmic media, and the forms of brand-building labour undertaken by cultural intermediaries like musicians, photographers, promoters and consumers.

The book traces the deepening entanglement between branding, popular music culture, and digital media technologies between 2005 and 2009. This period was an interesting one. Although I didn't really start out to track this at the time, part of what I was exploring was how the coolhunting tactics marketers developed in the 1990s were being integrated into the participatory and calculative digital media platforms that dominate branding today.

Malcolm Gladwell described coolhunting in his 1997 essay in The New Yorker. He wrote about two coolhunters who prowled the streets of hip urban neighbourhoods looking for ‘cool kids’ to find out what they did and what they thought. He sketched out a world of brand ethnography that developed alongside the explosive commercialisation of alternative and street culture in the 1990s:

Coolhunting is not about the articulation of a coherent philosophy of cool. It’s just a collection of spontaneous observations and predictions that differ from one moment to the next and from one coolhunter to the next. [The coolhunter] tries to construct a kind of grand matrix of cool… They go to each city and find the coolest bars and clubs, and ask the coolest kids to fill out questionnaires. The information is then divided into categories and subcategories [and sold to corporations].

During the 1990s a whole range of these agencies emerged to channel ‘cool’ into the planning decisions of major corporations. These agencies used a combination of ethnographic, focus group and street team tactics. Street teams involved recruiting cool kids to go ‘undercover’ in their cultural worlds to both promote products via word of mouth in their peer networks and to report back on cultural trends.

The coolhunting industry grew as brands sought to be more responsive and reflexive. Unable to direct the action of an increasingly fragmented market, command and control marketing gave way to flexible and just in time methods. Big corporations brought in the coolhunters to enable the positioning of brands within constantly evolving frameworks of meaning.

Douglas Rushkoff’s documentary The Merchants of Cool offers a great portrait of this late 1990s world of popular culture and branding. The film depicts the contradictions and clunkiness of coolhunting. In one scene a coolhunter runs a focus group with an unresponsive group of teenage boys, in another an MTV ethnographer rummages through the bedroom of a teenager asking him about the meaning of various possessions: his shirt, posters on his wall, CDs on his desk. It’s lame, and creepy.

The ‘data’ of cool was always problematic: you had to be cool to know cool, cool can’t be manufactured once you know what it is anyhow, once cool is observed it takes flight. The brand consultant and researcher Douglas Holt defined this problem for marketers as 'authenticity extinction'. Holt warned brands that coolhunting had a diminishing return because digging up, extracting and commodifying ‘authentic’ culture would eventually ‘exhaust’ the cultural resources that existed outside the market. Brands learnt though that authenticity was not a finite raw commodity. Coolness and authenticity are not intrinsic properties located in specific meanings. They are relational.

If authenticity was something always being produced via acts of recognition, rather than something located in unchanging essentialist cultural frameworks, then brands had to shift away from finding specific forms of cool to channel into corporate production. They had to move toward building an infrastructure for reflexively responding to the open-ended nature of cultural life. What emerged was a mode of branding that relies on the co-creative labour of cultural intermediaries and consumers. Smartphones and social media are useful to brands not only because of their data collection, analysis and targeting capacities, but also because they harness the productive labour of users who weave brands into affective portrayals of their identities and lived experience.

The coolhunting of the 1990s matters as an important historical anchor point for understanding branding today. It is an important moment where branding techniques emerge that do not construct brands not as discreet messages, but rather engineer them as open-ended social processes. Coolhunting might appear to be a process of finding some specific authentic meaning a brand can appropriate, but really it is a process of treating a brand as a modular cultural platform that can be endlessly reconfigured. Pop Brands examines how popular music culture works as a site where brands operate as open-ended social processes that depend on the creative labour of musicians, promoters, photographers and fans.

Real-world Activations

To operate as open-ended social process brands make themselves part of material cultural spaces like music scenes, venues, clubs and festivals. In Pop Brands I explore how brands create real world objects and spaces that harness and channel the creativity of musicians, photographers, promoters and fans. Brands investments in real world cultural space orchestrate a process through which people weave brands into mediated portrayals of their identities.

At summer Australian music festivals in the mid-2000s some of brand activations I documented included a Toohey's Extra Dry Snowdome, a Napoleon hair and make-up service, Virgin Mobile VIP bars and bathrooms, a Strongbow cider antique sailing ship and a Duracell battery water tank.

Many of these activations were experimental in the sense that they were part of a process through which market actors created and tested different methods for integrating brands into cultural events.

Below is one example of these experimental brand activations. Virgin Mobile built 'cone of silence' fibreglass domes at the Big Day Out music festival in Australia in 2006. The domes were soundproof containers that festival-goers could stand in to make phone calls during the loud and chaotic music festival. The domes expressed the playful character of the Virgin brand, which might have excused their slightly ridiculous impracticality. The big problem for mobile phone users at festivals in the mid-2000s was not finding a quiet place to make a call, but getting bandwidth. The use of phones by the enormous crowd at festivals crashed local phone networks.

Over a decade later, the domes are interesting because they offer one small illustration of how brands experimented with making themselves part of the infrastructure of cultural spaces and events. These material objects orchestrate playful engagements with consumers. The brand moves away from making a definite symbolic claim about the qualities of the brand, and instead builds a material object that consumers engage with as part of their lived cultural practices. The brand becomes part of the infrastructure of cultural life, and the range of qualities consumers attach to it become more flexible.

While these brand objects frequently appeared to fail in the sense that they had no practical purpose, in the longer run they succeeded as part of an ongoing sequence of experiments that linked brands, cultural spaces and digital media together. Over time, this enabled brands to operate as much more open-ended and modular market processes.

The 'cone of silence' fibreglass domes provided by Virgin Mobile at the Big Day Out, 2006.

Smartphones and brand activations

Before smartphones and social media the reach of brand activations in material cultural spaces was limited to the peer networks and word of mouth of people attending the events. The engagement with the brand was confined to the music festival or club in which it took place.

Pop Brands documents in part how the arrival of digital cameras, feature phones and then smartphones in the mid-2000s set off a process through which real-world brand activations became integrated with the commercial logic of social media. Brand activations gradually became devices for getting consumers to use their smartphones to generate media content and data on social media platforms.

Music festivals were a key site for this experimentation because they were a cultural space where fans rapidly adopted digital cameras and smartphones to document live experiences and share them with peers. The image below is from the V festival in 2007. The lead singer of the indie rock band Phoenix has jumped into the crowd. Fans rush toward him, both pushing to get near him and also to photograph him using digital cameras. Photos and videos of this moment circulated widely on social media platforms like Facebook and YouTube.

In this period where digital cameras and smartphones became ubiquitous devices the ritual of live music experience changed dramatically. Where once cameras were a rarity at live music events, they rapidly became a standard part of enjoying a live performance. Live music performances are now characterised by a sea of raised smartphones capturing images and videos of affectively intense moments in a performance.

Thomas Mars from the band Napoleon jumps into the crowd at the V festival Australia, 2007.

Brands used activations at music festivals to stimulate and encourage the use of digital cameras and smartphones as part of the experience. In 2006 Nokia's Music Goes Mobile promotion worked with bands and fans to use Nokia feature phones to create and share video of live music events. At the V festival in 2007 Virgin Mobile set up a large video screen in partnership with Sony Ericsson and Nokia at the main stage and invited festival-goers to send images to the screen using the new MMS function of camera-enabled feature phones. At the Big Day Out music festival in 2009 HP set up a Go Live activation that enabled fans to download images from their digital cameras and upload them to their Facebook or MySpace profiles during the festival.

Each of these activations attempted to enable, encourage and instruct music fans to use their devices to create and share images of their cultural experiences in real time.

These activations were also experimental, and often not entirely successful. In the case of Virgin Mobile's interactive screens at the V Festival that are pictured below, few people had a phone with a decent camera. For those who did, it cost several dollars to send an image and it was hard to get the bandwidth to send it. Despite this, it is important as an example of an early prototype for getting festival-goers to create images and immediately share them on digital media platforms.

These were important experiments because they illustrate how brands were beginning to think about how they might translate their engagement with consumers in real world cultural spaces to the emerging mobile and social web. They demonstrate how brands were important actors in the engineering of the interface between the social web and material cultural life.

Screens at the V festival Australia that fans could send images to using the MMS function of feature phones, 2007.

In addition to elaborate installations like interactive screens, branded objects began to take on new uses. The image below of a Virgin branded beach ball at the V festival is one example of how brand iconography bouncing around the festival site got caught up in images that festival-goers created of their experience. As digital cameras and smartphones became ubiquitous, cultural events like music festivals became sites for the production of streams of brand imagery. Brands worked to both stimulate the creation of media content form cultural events by musicians, creatives and consumers and to create purpose-built themed spaces featuring brand iconography that framed the images people created and shared.

A beach ball in the crowd at the V festival Australia, 2007.

During this period brands deliberately went about making themselves as durable and visible part of the infrastructure of cultural space. In doing so, they established a series of market devices that inculcate consumers in the creation of brand imagery as a by-product of creating and sharing images of everyday life on social media platforms. Importantly, as brands began to operate as cultural resources consumers could work with and incorporate within their own narratives, they became much more symbolically open-ended. A brand could be attached to whatever meanings and qualities cultural actors like musicians or music fans attached to it as they 'played' with it as part of their cultural and media-making experiences.

Pop Brands tracks a range of these brand engagements with material cultural events during this period including Coca-Cola's Coke Live, Nokia's Terminal 9 and Music Goes Mobile, HP's Go Live and Jagermeister's Uprising.

Media experiments

From the mid-2000s brands were important actors in imagining and experimenting with the possibilities of social and mobile media. Between 2004 and 2006 Coca-Cola ran a campaign called ‘Coke Live’ in Australia. Similar campaigns were run in countries throughout the world.

The campaign included live music gigs and an interactive website. Coca-Cola ran large all-ages live music concerts in capital cities around Australia. This was a serious investment: free gigs in stadium arenas featuring some of Australia’s most popular bands. The gigs made the brand a material cultural experience. The material cultural experience of the gig was also leveraged as an opportunity to engage with fans on the emerging social media platforms.

A screen shot of the Australian Coke Live website, 2006.

The website Coke built in 2006 as part of Coke Live is illustrates how brands were attempting to ‘imagine’ the trajectory of social and mobile media. With the website they created a simulation of what they couldn’t quite realise in real life: seamless interconnection between real world cultural events, brands and digital media.

The website simulated a music festival. Consumers had to register and build a digital avatar who ‘attended’ the festival. The avatar was constructed out of a series of symbolic resources that the brand made available: gender, skin colour, hair style, clothes. The combinations enabled consumers to express themselves within a limited range of pre-determined cultural categories – in the coolhunter language of 2006 – skaters, emos, surfers, indie rockers.

Building the avatar involved answering up to 100 questions like ‘where do you hang out with friends?’ and ‘what bands do you listen to?’

The more questions young consumers answered the more resources were made available for them to fashion their cultural identity. They might acquire a skateboard, surfboard, cooler sneakers, a branded hoodie, or an oversized clock to hang around their neck.

Participants had to answer the questions in order to earn enough points to get tickets to the concert. Once the avatar was built consumers entered the festival site. They could move about the site going to various music stages where they could access exclusive content like videos of live performances, interviews, and interact via chat with other avatars on the site.

In practice, the site was clunky. It is hard to get young people to fill out questionnaires to build an avatar, and once logged on to the virtual music festival there weren't very many avatars there 'partying' and no established cultural codes for finding friends or interacting with strangers.

In terms of imagination however, the brand was headed in the right direction. The website offers a neat example of branding as an open-ended process of experimentation and innovation. The things that brands are experimenting with today point us toward the infrastructure they are building for tomorrow.

The website was in some important ways a prototype for the configuration of brand-funded social media that dominates our media system today.

The website was organised around the collection of personal information and expressions for use by brands to flexibly configure their marketing strategies.

The website guided users through the production of a visual representation of the self, built in part from the cultural and symbolic resources of commercial popular culture. Alison Hearn calls this the construction of a ‘branded self’. There are two elements here: using brands as symbolic resources in the construction of our own identities and borrowing the promotional logic of brands in the way we position and present ourselves in competitive ways. This creates seamless links back and forth between the material cultural world, the performance of our own identities, brands and social media.

The website simulated the integration between the mediation of everyday life and the real world activities of brands. Coke were imagining a music festival where the audience generated a continuous stream of content and data about the experience. That is now exactly what festivals and many other cultural events look like. The web-enabled mobile device and the live and flowing social media platform enabled this. In 2006 Coke could only simulate a moment that is now an integrated part of the infrastructure of cultural events like music festivals.

Affecting one another

A Jack Daniel's sponsored bus that the alternative rock bands travelled on at the Big Day Out Australia, 2006.

Brands that operate as open-ended social processes rely on cultural actors like musicians, photographers, promoters and consumers to do the labour of creating brand value. As cultural producers and consumers incorporate brands into their own identities they do the work of making brands a durable part of cultural life. The work of brand management then shifts away from prescribing the specific meanings that make up brands, and toward constructing the cultural infrastructure within which a diverse range of cultural actors create brand value.

In Pop Brands I document how brands narrate their involvement in cultural life as meaningful and empowering, they present themselves as supporters of cultural events. Musicians both use these claims as an alibi for their involvement in brand campaigns, and simultaneously distance themselves from any explicit or sincere endorsement of the brand. Alcohol brands in particular like Jack Daniel's, Jagermeister, and Tooheys beer ran initiatives that gave alternative or independent musicians access to record deals, media exposure, gigs and tours. The Jack Daniel's bus pictured above carried alternative bands on the Big Day Out tour in 2006. These investments by brands were often welcomed by musicians, particularly given the dramatic change in the music industry at the time as a result of collapsing record sales.

The relationship between brands, musicians and fans are complicated. Brands appear to thrive regardless of whatever specific meaning musicians or fans attach to them. What matters above all else is that the brand is paid attention and incorporated into the cultural processes through which musicians and fans affect one another. The cultural labour of co-creating brands generated value not via sincerely attaching prescribed or specific authentic meanings to a brand, but rather in the general capacity to create relations of affect and attention of which brands are a part.

The relationships between brands, musicians and fans illustrate how brands operated as open-ended cultural processes. The brands I examine in Pop Brands most often made no specific requests for endorsements from musicians as part of their partnerships. And, musicians would often openly distance themselves, ironically endorse, or even make fun of the brand.

What this suggests is that brands don't require musicians to attach a particular quality to the brand. Musicians do not need to perform a certain aesthetics prescribed by the brand, they simply need to capture and channel the action, attention and affects of music fans, whatever they may be. In this cultural setting the counter-cultural and alternative culture concept of 'selling out' loses its purchase as a form of cultural critique. Brands thrive even in a setting where they are being given ironic and disdainful treatment. What matters above all else is that they are being paid attention and incorporated into cultural practices of being seen and felt. Music culture becomes valuable to brands not because it embodies specific ideas and qualities brands want to appropriate, but rather because it is a domain where affects are induced, circulated, and chanelled through bodies and onto digital media platforms. Brands harness the general capacity of musicians, fans and other cultural labourers to incorporate them in the general circulation of meaning, affect and attention in a digital culture.

Brands are Cultural Infrastructure

A tent featuring live DJ performances and selling Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes at the V festival Australia 2007.

Pop Brands argues that brands can no longer be understood only in straight-forward ideological terms - as a process of controlling the making and circulation of specific meanings. They must also be understood in infrastructural terms. That is how they construct the material spaces and devices that orchestrate, harness and channel the performances and relationships through which we affect one another.

The image above depicts an all white dance tent at the V festival in 2007. The tent featured DJs and promotional labourers who sold Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes. There is no advertisement for cigarettes taking place in this tent, no brand logos, no slogans or symbolic imagery. But, the tent does construct an affective atmosphere where cigarettes are embedded within the enjoyment of a music festival and the translation of that experience into images using digital cameras and social media. Brand value is constructed via the open-ended practice of incorporating the commodity into the performance of cultural life. The devices of this mode of branding are a tent, a DJ, lighting, amplification, digital cameras and intoxicated bodies.

Brands aim to channel our capacity to judge, pay attention and affect one another. They construct and fund the cultural and digital infrastructure that we use to mediate our lives and identities. They make themselves a durable part of our cultural atmosphers, so that as we go about mediating our lives we simultaneously mediate brands. The brand becomes a flexible and modular filter for our own self-expression. This means critical accounts of branding need to get both more ethnographic and more technically literate. Critiquing not just what brands have to say, but carefully explaining how brands organise our cultural worlds and communicative lives by connecting together material cultural space with emerging digital media technologies.